As scientists continue working to develop medications and search for tools to help individuals elude Scientists traditionally have looked at Alzheimer’s disease almost exclusively as a chronic brain dysfunction, caused by a recalcitrant protein known as beta-amyloid.

Researchers have fallen into “an intellectual rut” by singularly focusing on beta-amyloid as the genesis of Alzheimer’s, says Donald Weaver, a chemistry professor and director of the Krembil Research Institute, University Health Network, at the University of Toronto. Devoting all efforts at subduing beta-amyloid — with medications like the controversial Aducanumab — has blunted the search for other factors that might be spawning the disease.

“Alzheimer’s is a public health crisis in need of innovative ideas and fresh directions, “ Weaver maintains. Fortunately, he reports, the tide seems to be turning on scientific research for the disease. With scientists failing to come up with an effective therapy to treat Alzheimer’s by blocking the amyloid protein, they are beginning to look for new approaches.

Weaver is encouraged by this research that goes beyond the beta-amyloid protein.

Some, he says, believe that bacteria from the mouth causes a brain infection resulting in Alzheimer’s. Other scientists are looking at mitochondria – the minute cellular structures that provide energy for cognitive functions of the brain – as possibly causing Alzheimer’s. Still others think the disease may stem from the way the brain handles certain metals.

“It is gratifying to see new thinking about this age-old disease,” he says.

Weaver and his team at the Krembil Research Institute have developed their own theory on Alzheimer’s.

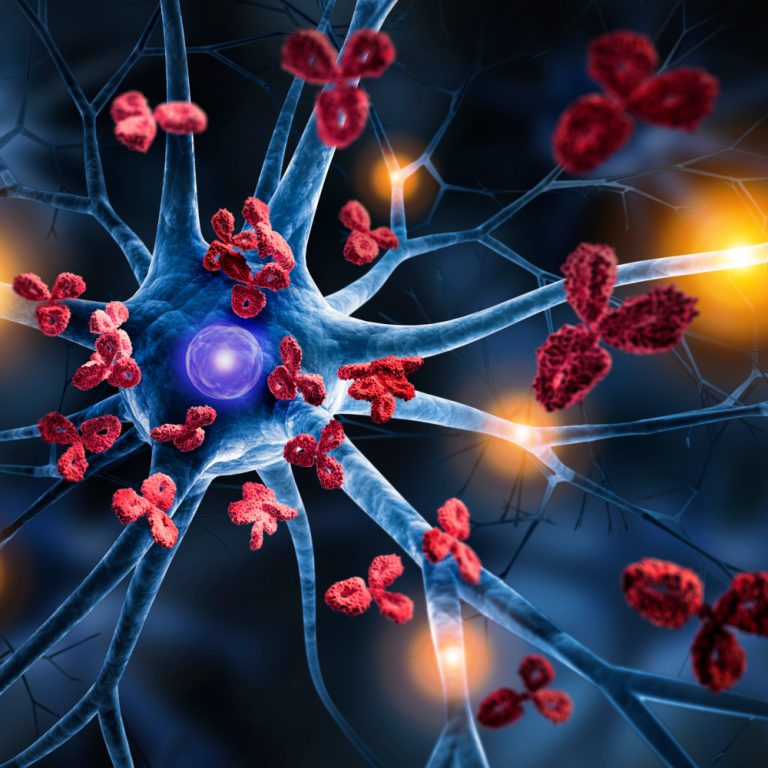

“Based on our past 30 years of research,” Weaver writes, “we no longer think of Alzheimer’s as primarily a disease of the brain. Rather, we believe that Alzheimer’s is principally a disorder of the immune system within the brain.”

Beta-amyloid, rather than being an abnormally produced protein in the brain, according to Weaver, is one of the keys to the brain’s immune system. “It is supposed to be there,” he says.

The problem arises, Weaver suggests, when beta-amyloid cannot differentiate between the brain cells it is supposed to protect and incoming bacteria that it is supposed to ward off. When that confusion emerges, the beta-amyloid protein “mistakenly attacks the very brain cells it is supposed to be protecting.”

Those attacks chronically and progressively cause brain deterioration and lead to dementia, according to Weaver. This classifies Alzheimer’s as an autoimmune disease, he says.

While other autoimmune diseases, such as arthritis, can be countered with steroid therapies, Alzheimer’s cannot, Weaver says.

Yet he sees hope for using other therapies to treat Alzheimer’s as an autoimmune disease.

“We strongly believe that targeting other immune-regulating pathways in the brain will lead us to new and effective treatment approaches for the disease,” he says.